2. Description of the Survey

2.1 Sample Design

The respondent universe for the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is the civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 years or older residing within the United States. The survey covers residents of households (e.g., individuals living in houses or townhouses, apartments, and condominiums; civilians living in housing on military bases) and individuals in noninstitutional group quarters (e.g., shelters, rooming or boarding houses, college dormitories, migratory workers’ camps, halfway houses). Excluded from the survey are individuals with no fixed household address (e.g., homeless and/or transient people not in shelters), active-duty military personnel, and residents of institutional group quarters, such as correctional facilities, nursing homes, mental institutions, and long-term care hospitals.

2.1.1 Coordinated Sample Design for 2014 through 2022

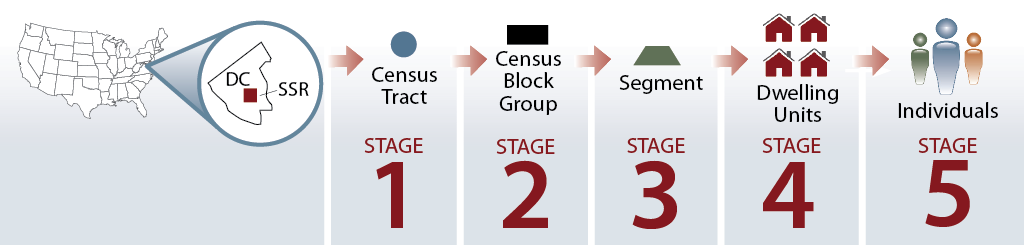

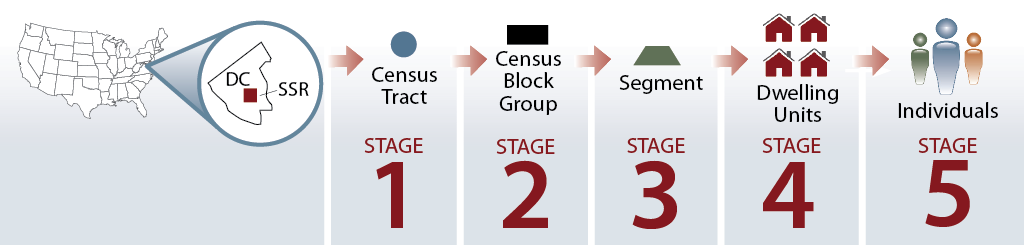

A coordinated sample design was developed for the 2014 through 2022 NSDUHs. The coordinated sample design is state-based, with an independent, multistage area probability sample within each state and the District of Columbia. States were the first level of stratification. As shown in Figure 2.1, each state was further stratified into approximately equally populated state sampling regions (SSRs). Creation of the multistage area probability sample then involved selecting census tracts within each SSR (Stage 1), census block groups within census tracts (Stage 2), and area segments (i.e., a collection of census blocks) within census block groups (Stage 3). Finally, dwelling units (DUs) were selected within segments (Stage 4), and (within each selected DU) up to two residents who were at least 12 years old were selected for the interview (Stage 5).

The coordinated sample design for 2014 through 2022 includes a 50 percent overlap in third-stage units (area segments) within each successive 2-year period from 2014 through 2022. DUs not sampled the first year are eligible for selection the following year. There is no planned overlap of sampled residents. However, individuals may be selected in consecutive years if they move and their new residence is selected the year after their original DU was sampled. The planned overlap in area segments reduces annual costs. When trend data are reported, this sample overlap also slightly increases the precision of estimates for year-to-year trends because of the expected small but positive correlation resulting from the overlapping area segments between successive survey years.

The 2014 through 2022 NSDUH sample design provides sufficient sample sizes to support state and national estimates. The cost-efficient sample design allocates completed interviews (and associated sample) to the largest 12 states approximately proportional to the size of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 or older in these states. In the remaining states, a minimum sample size is required to support reliable state estimates by using either direct methods (by pooling multiple years of data) or small area estimation.2 Population projections based on the 2010 census and data from the 2006 to 2010 American Community Surveys (ACSs) were used to construct the sampling frame for the 2014 through 2022 NSDUHs.

Table 2.1 at the end of this chapter shows the targeted numbers of completed interviews in selected states per year for the 2014 through 2022 samples.3 For Hawaii, the sample was designed to yield a minimum of 200 completed interviews in Kauai County, Hawaii, over a 3-year period. To achieve this goal while maintaining precision at the state level, the annual sample in Hawaii consists of 67 completed interviews in Kauai County and 900 completed interviews in the remainder of the state, for a total of 967 completed interviews each year for 2014 onward. The sample design also targeted 960 completed interviews in each of the remaining 37 states and the District of Columbia that are not listed individually in Table 2.1.

2.1.1.1 Selection of Area Samples and Dwelling Units within States

As mentioned previously, states were first stratified into SSRs. The number of SSRs varied by state and was related to the state’s sample size. SSRs were contiguous geographic areas designed to yield approximately the same number of interviews within a given state.4 A total of 750 SSRs are in the 2014 through 2022 sample design. Table 2.1 also shows the number of SSRs for different states.

The first stage of selection for the 2014 through 2022 NSDUHs was census tracts.5 Within each SSR, 48 census tracts6 were selected with probability proportional to a composite measure of size.7 This stage was included to contain sampled areas within a single census tract to the extent possible in order to facilitate merging to external data sources. Within sampled census tracts, adjacent census block groups were combined as necessary to meet the minimum DU size requirements.8 One census block group or second-stage sampling unit then was selected within each sampled census tract with probability proportional to population size. The selection of census block groups at the second stage of selection is included to facilitate possible transitioning to an address-based sampling design in a future survey year. For the third stage of selection, adjacent blocks were combined within each sampled census block group to form area segments. One area segment was selected within each sampled census block group with probability proportionate to a composite measure of size.

Although only 40 segments per SSR were needed to support the coordinated 9-year sample for the 2014 through 2022 NSDUHs, an additional 8 segments per SSR were selected to support a number of large field tests.9 Eight sample segments per SSR were fielded during the 2020 survey year. Four of these segments were selected for the 2019 survey and were used again in the 2020 survey; four were selected for the 2020 survey and will be used again in the 2021 survey.

Sampled segments for 2020 were allocated equally into four separate samples, one for each 3-month period (calendar quarter) during the year. That is, a sample of addresses was selected from two segments in each calendar quarter.10 In each of the area segments, a listing of all addresses was made, from which a national sample of 642,549 addresses was selected. Of the selected addresses, 536,203 were determined during the field period to be eligible sample units. In these sample units (which can be either households or units within group quarters), sampled individuals were randomly selected using an automated screening procedure programmed in the handheld tablet computers carried by the field interviewers (FIs) or in the web screening questionnaire (see Sections 2.2.1.1 and 2.2.1.3). The number of sample units completing the screening was 90,937.

2.1.1.2 Selection of People within Dwelling Units, by Age Group

As shown in Table 2.2, the allocation of the 2014 through 2022 NSDUH samples is 25 percent for adolescents aged 12 to 17, 25 percent for young adults aged 18 to 25, and 50 percent for adults aged 26 or older. The sample of adults aged 26 or older is further divided into three subgroups: aged 26 to 34 (15 percent), aged 35 to 49 (20 percent), and aged 50 or older (15 percent). Table 2.2 at the end of this chapter provides the target sample allocations for the 2014 through 2022 NSDUHs. Adolescents aged 12 to 17 years and young adults aged 18 to 25 years are oversampled.

2.1.2 Special Changes to the 2020 Sample Design

The sample design included two special changes for the 2020 NSDUH:

- expansion of the sample to support a special clinical validation study (CVS), and

- changes to the sample design in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

The first of these changes was planned before the start of 2020 NSDUH data collection. The second change was necessitated by the limitations that the COVID-19 pandemic imposed on in-person data collection.

2.1.2.1 Clinical Validation Study Sample

The CVS was originally planned for the first 6 months of the 2020 NSDUH to assess a revised NSDUH section on substance use disorders (SUDs) according to the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). To support this study, the national sample size of 67,507 interviews was supplemented with 1,500 interviews proportionally allocated to states and age groups in Quarters 1 and 2 (i.e., January to June 2020). Including the supplement, the expanded target sample size for the 2020 NSDUH was 69,007 interviews. From the expanded sample, 1,500 respondents were expected to be selected for the CVS based on their responses to selected questionnaire items (see Table 2.1). Logic in the NSDUH questionnaire then assigned respondents selected for the CVS sample to receive the DSM-5 SUD questions. Table 2.2 shows the target sample allocation for the CVS by age group. Because the CVS supplemental sample was allocated proportionally to the overall NSDUH population, the age group allocation differed from the 2014 through 2022 target samples. As described in Section 2.1.1.2, the sample design for the main survey oversampled adolescents aged 12 to 17 and young adults aged 18 to 25.

All other respondents received the standard set of NSDUH SUD questions that used criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (APA, 1994). Sections 2.2.1.2 and 2.2.2.2 provide more information about the data collection procedures and questionnaire differences for the CVS.

2.1.2.2 Sample Design Changes Because of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Given the public health emergency related to COVID-19 and considering the safety of field staff and the public, NSDUH in-person data collection was suspended on March 16, 2020, including the CVS.11 To assess the feasibility of resuming in-person data collection, a limited sample was fielded for a small-scale data collection from July 16 to 22, 2020, in selected counties within two states where in-person data collection was deemed to pose a low risk of COVID-19 transmission and infection based on state- and county-level health metrics. For the remainder of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic made it nearly impossible to collect data in person. To mitigate the effect on respondent sample size, web-based data collection was added and Quarter 4 became a period of multimode data collection. For the resumption of data collection in Quarter 4, all sample dwelling units (SDUs) originally selected from the Quarter 2, 3, and 4 area segments for in-person data collection were released for web or in-person data collection. SDUs in the Quarter 2, 3, and 4 area segments were released for in-person data collection in counties where the risk of COVID-19 transmission and infection was deemed to be low beginning on October 1, 2020. SDUs in the remaining Quarter 2, 3, and 4 area segments (except in segments that were worked by FIs during the 1-week, small-scale data collection) were mailed an invitation to participate via the web beginning on October 30, 2020. Additional SDUs also were selected in some segments from Quarters 2 and 3 and released to web-based data collection in Quarter 4 to partially compensate for the negative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on data collection and response rates. See Section 2.2.1.3 for information on web-based data collection, including the situation in which sampled areas were transferred to web-based data collection because they became ineligible for in-person data collection.

2.1.3 Sample Results for the 2020 NSDUH

In 2020, the actual sample sizes in the 12 largest states12 ranged from 752 to 2,193. In the remaining states, the actual sample sizes ranged from 352 to 723. These sample sizes included the additional respondents for the CVS supplemental sample in Quarter 1. For specific sample sizes by state, see the 2020 sample experience report (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2021g).

Adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2020 were sampled at an actual rate of 81.4 percent, and young adults aged 18 to 25 were sampled at a rate of 70.2 percent on average, when they were present in the sampled households or group quarters. Adults were sampled at rates of 35.5 percent for adults aged 26 to 34, 30.5 percent for adults aged 35 to 49, and 12.4 percent for adults aged 50 or older on average. The overall population sampling rates in 2020 were 0.025 percent for 12- to 17-year-olds, 0.027 percent for 18- to 25-year-olds, 0.015 percent for 26- to 34-year-olds, 0.013 percent for 35- to 49-year-olds, and 0.006 percent for those 50 or older.13 Nationwide, 62,515 individuals were selected. Of these selected individuals, 17,082 completed the interview in person and 19,202 completed the interview via the web. Consistent with previous surveys in this series, the final respondent sample of 36,284 individuals was weighted to be representative of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 or older. In addition, state samples were weighted to be representative of their respective state populations. See Section 2.3.4 for details on weighting. More detailed information on the disposition of the national screening and interview sample can be found in Chapter 3 of this report. More information about the sample design can be found in the 2020 NSDUH sample design report (CBHSQ, 2021f).

2.2 Data Collection Methodology

This section discusses the data collection procedures and questionnaire changes for the 2020 NSDUH.

- Section 2.2.1 discusses in-person data collection procedures (including modifications to in-person data collection procedures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic), data collection procedures for the CVS, and web-based data collection in Quarter 4 (October to December).

- Section 2.2.2 discusses questionnaire changes that were implemented for the entire 2020 data collection period, changes for the CVS, changes in Quarter 4 regardless of whether interviews were completed in person or via the web, and specific changes to accommodate web-based data collection in Quarter 4.

2.2.1 Data Collection Procedures

Data collection methods were modified during 2020 due to the public health emergency related to COVID-19 to ensure the safety of the public and FIs. Quarter 1 (January to March 2020) was completed using standard NSDUH protocols with in-person data collection. However, Quarter 1 data collection ended 15 days early when work was suspended on March 16, 2020. NSDUH project management at RTI began working closely with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and RTI’s Infectious Disease Response Team (IDRT), Executive Leadership Team (ELT), and Institutional Review Board (IRB) to determine when and where it would be safe to resume in-person data collection.

To assess the feasibility of resuming in-person data collection, the IDRT advised conducting a small-scale data collection effort. SAMHSA, the ELT, and the IRB approved a 1-week small-scale data collection effort that was conducted from July 16 to 22, 2020. Revisions were made to protocols, processes, and materials to ensure the safety of respondents and FIs. Section 2.2.1.1.2 provides information on revisions to protocols. Analysis of the data and results of a debriefing session with FIs indicated that overall, the safety procedures used during the small-scale data collection effort did not have a negative effect on respondents’ willingness to participate in the survey and FIs were overall pleased with these measures.

Data collection resumed in Quarter 4, but in-person data collection was limited to a small number of eligible states and counties due to COVID-19 infection rates. Web-based screening and interviewing procedures were developed (Section 2.2.1.3) to account for suspended data collection in Quarter 2 and most of Quarter 3 and to maximize the number of completed interviews for national estimates. NSDUH data collection in Quarter 4 used in-person and web-based procedures.

2.2.1.1 In-Person Data Collection

2.2.1.1.1 Standard In-Person Data Collection Procedures

The standard data collection methods used for NSDUH to conduct in-person interviews with sampled individuals incorporate procedures to increase respondents’ cooperation and willingness to report honestly about sensitive topics, such as illicit drug use behavior and mental health issues. Confidentiality is stressed in all written and oral communications with potential respondents. Respondents’ names are not collected with the data, and computer-assisted interviewing (CAI) methods are used to provide a private and confidential setting to complete the interview. Data collection procedures are approved by RTI’s IRB before the start of data collection. Adults aged 18 or older must consent to provide basic data on characteristics of household members (screening) or to complete the main interview. If an adolescent aged 12 to 17 is selected for the main interview, permission from a parent or adult guardian and assent from the selected adolescent must be obtained for the adolescent to complete the interview.

Introductory letters are sent to sampled addresses, followed by an FI visit. FIs make multiple attempts, if necessary, at different days and times to contact the DU. When contacting a DU, the FI asks to speak with an adult resident (aged 18 or older) of the household who can serve as the screening respondent. To obtain basic demographic data on all household members aged 12 or older who lived at the address for most of the calendar quarter, the FI uses a handheld tablet computer to ask the screening respondent a series of questions taking about 5 minutes to complete. The tablet computer then uses the demographic data in a preprogrammed selection algorithm to select zero, one, or two individuals for the interview, depending on the composition of the household. This selection process is designed to provide the necessary sample sizes for the specified population age groupings.

In areas where a third or more of the households contain Spanish-speaking residents, the initial introductory letters written in English are mailed with a Spanish version printed on the back. All FIs carry copies of the introductory letter in English and Spanish. If FIs are not certified bilingual in English and Spanish, they will use preprinted Spanish cards to attempt to find someone in the household who speaks English and who can serve as the screening respondent or who can translate for the screening respondent. If no one is available, the FI’s field supervisor will schedule a time when a certified bilingual FI can come to the address. In households where a language other than Spanish is encountered, another language card is used to attempt to find someone who speaks English to complete the screening.

The NSDUH interview can be completed in English or Spanish, and both versions have the same content. If the sampled person prefers to complete the interview in Spanish, a certified bilingual FI is sent to the address to conduct the interview. Because the interview is not translated into any other language, if a sampled person does not speak English or Spanish, the interview is not conducted.

Immediately after completion of the screener, FIs attempt to obtain consent and conduct the NSDUH interview with each sampled person in the household. The FI asks the respondent to identify a private area in the home in which to conduct the interview away from other household members. The FI uses a laptop computer to conduct the interview, which averages about an hour and includes a combination of computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). In the CAPI portion of the interview, the FI reads the questions to the respondent and enters the answers into the computer. In the ACASI portion of the interview, the respondent reads questions on the computer screen or listens to questions through headphones, then keys in answers directly into the computer without the FI knowing the response.

The NSDUH in-person interviews begin in the CAPI mode and consist of initial demographic questions. The interview then transitions to the ACASI mode for the sensitive questions (e.g., use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs14). Additional self-administered interview sections15 follow the substance use questions and ask about a variety of sensitive topics (e.g., injection drug use, SUDs, substance use treatment, mental health issues, use of mental health services, important emerging substance use and mental health issues, perceived effects of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Although many of the questions about mental health issues are asked both of youths aged 12 to 17 and of adults, some are asked only of adults, and others are asked only of youths. Definitions for many of the terms for substance use and mental health measures from the survey are included in the glossary in Appendix A of this report.

Additional demographic questions addressing topics such as immigration, current school enrollment, and employment and workplace issues are included at the end of the ACASI section for in-person interviews. Finally, the in-person interviews return to the CAPI administration for questions on the household composition, the respondent’s health insurance coverage, and the respondent’s personal and family income. Each respondent who takes the time to complete a full interview is given a $30 cash incentive as a token of appreciation.

No information directly identifying a respondent is captured in the in-person CAI record. FIs transmit completed interview data to RTI in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. Screening and interview data are encrypted while they reside on the laptop and tablet computers. Data are transmitted back to RTI on a regular basis using a wireless connection to the Internet. All data are encrypted while in transit across Internet connections. In addition, in-person screening and interview data are transmitted back to RTI in separate data streams and are kept physically separate (on different devices) before transmission occurs.

After in-person data are transmitted to RTI, certain respondent records are selected for verification. Respondents are contacted by RTI to verify the quality of an FI’s work based on information respondents provide at the end of screening (e.g., if no one is selected for an interview or all household members at the sampled address are ineligible for the study) or at the end of the interview. For the screening, adult household members who served as screening respondents provide their first names and telephone numbers to FIs who enter the information into tablet computers and transmit the data to RTI. For completed interviews, respondents write their telephone numbers and mailing addresses on quality control forms and seal the forms in preaddressed envelopes FIs mail back to RTI. All contact information is kept completely separate from the answers provided during the screening or interview.

Samples of respondents who completed screenings or interviews are randomly selected for verification. These respondents are called by telephone interviewers who ask scripted questions designed to determine the accuracy and quality of the data collected. Any sampled screening or interview discovered to have a problem or discrepancy is flagged and routed to a small specialized team of telephone interviewers who recontact respondents for further investigation of the issue(s). Depending on the amount of an FI’s work that cannot be verified through telephone verification, including bad telephone numbers (e.g., incorrect number, disconnected, not in service), a field verification may be conducted. Field verification involves another FI returning in person to the sampled address to verify the accuracy and quality of the data. If the verification procedures identify situations in which an FI falsified data, the FI is terminated from employment. All screenings or interviews completed that quarter by the falsifying FI are verified by the FI conducting the field verification and are reworked.

2.2.1.1.2 Modifications to In-Person Data Collection Procedures Because of the COVID-19 Pandemic

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, RTI’s IDRT developed eligibility criteria for in-person data collection based on COVID-19 infection rates and state government mandates, such as stay-at-home orders. The criteria were based on state- and county-level infection rates. The 2020 data collection final report (CBHSQ, forthcoming b) will provide details on the specific state- and county-level criteria that were applied to in-person data collection in July 2020 and again from October 1 to December 31, 2020.

The general procedures for in-person data collection described in Section 2.2.1.1.1 typically applied when in-person data collection resumed, including procedures for transmitting completed interviews to RTI and for verification. However, revisions needed to be made to in-person protocols, processes, and materials to protect the health and safety of respondents and FIs. The revisions included providing FIs with the following: (1) RTI-issued masks, gloves, disinfecting wipes, and hand sanitizer for use during data collection; (2) a NSDUH Safety Protocol Reference Guide that outlined all required safety procedures; and (3) a risk information form provided to all respondents. Examples of the safety protocol reference guide and the risk information form will be provided in the 2020 data collection final report (CBHSQ, forthcoming b). These revised procedures were used in the 1-week small-scale data collection effort in July 2020 and during Quarter 4.

During the 1-week in-person data collection in July 2020, NSDUH FIs who approached a DU to conduct a screening were required to wear a disposable face mask and keep 6 feet of distance between themselves and others when possible. FIs were asked to encourage respondents (or potential respondents) to wear a mask, but respondents were not required to do so. After a brief introduction and confirmation that the address was correct, FIs completed the informed consent procedures for the screening and handed each respondent a study description. FIs placed all materials to be handed to respondents in a plastic sleeve 3 days prior to use. For Quarter 4, this procedure was updated to require FIs to place materials in separate folders 3 days prior to use: one folder for each DU screening and separate folders for each interview respondent.

In both July 2020 and Quarter 4, a new requirement for informed consent due to COVID-19 was to provide each respondent with a printed copy of the COVID-19 risk information form to keep. FIs and respondents reviewed the content of this form together to be sure each potential respondent was aware of the risks associated with participation in NSDUH and to allow each person to make an informed decision about participating in the study due to the potential risks of COVID-19 transmission and infection.

If a DU member was selected to complete the interview, the FI was encouraged, when possible, to recommend conducting the interview outside of the home, such as on a porch, deck, or patio. This procedure was recommended so the FI would avoid entering people’s homes for a prolonged period of time. While setting up the laptop computer for the interview after the respondent had consented to participate, the FI, in the presence of the respondent, used disinfectant wipes to clean the surface of the laptop, including the keyboard, the headphones, and the Showcard Booklet.

Unlike regular in-person data collection, FIs did not attempt follow-up refusal conversion. Records were assigned a final code as a refusal for screening or interview immediately if a DU member mentioned COVID-19 as a concern. If there was no contact with anyone in the household, in-person attempts were limited to 10 visits. In addition, revisions were made to the NSDUH FI authorization letter that FIs carry with them in the field to designate FIs as “essential workers.”

2.2.1.2 Clinical Validation Study Data Collection

During the first 3 months16 of the 2020 NSDUH main study data collection, the CVS was also conducted to assess a revised SUD module developed by SAMHSA for inclusion in the NSDUH main study questionnaire. Sections 2.2.2.2 and 3.4.3.4 provide more information on the development and content of the CVS questions.

Respondents were eligible for the CVS sample if they chose to answer the NSDUH main study interview questions in English17 and did not break off the interview before beginning the SUD module.18 The CVS sample was selected by the NSDUH CAI instrument. Based on their responses to questions about past year use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, respondents selected for the CVS were routed to the new DSM-5 SUD module instead of the DSM-IV module. Otherwise, CVS sample members completed the main study modules in the same order as the non-CVS sample.19

At the end of the NSDUH main study interview, CVS sample respondents were invited by the FIs to participate in a follow-up clinical interview. NSDUH main study respondents who agreed to participate in the follow-up interview and provided relevant contact information were part of the CVS follow-up sample.

The follow-up clinical interviews were completed via telephone within 2 to 4 weeks of the NSDUH main study interview. The follow-up interviews were conducted using a modified paper version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV) (First et al., 2015). The SCID is a semi-structured diagnostic interview used to assess psychiatric disorders according to the criteria in DSM-5. As a semi-structured clinical interview, the SCID contains structured, standardized questions that are read verbatim and sequentially, combined with unstructured follow-up questions that the clinical interviewer tailors to the respondent based on clinical judgment and the respondent’s answers. The SCID was administered over the telephone by clinical interviewers who underwent 4 days of extensive training with clinical supervisors and Dr. Michael First, the SCID’s developer from Columbia University. Within 48 hours after completing an interview, the clinical interviewer edited and shipped the paper SCID to RTI for final editing and keying in-house.

2.2.1.3 Web-Based Data Collection

As noted previously, SAMHSA decided to suspend NSDUH in-person data collection on March 16, 2020, due to the COVID-19 public health emergency. To facilitate data collection while minimizing risks to respondents and FIs, SAMHSA approved the addition of web-based data collection starting in Quarter 4 (October to December 2020).

Web-based data collection in NSDUH followed the same basic steps as in-person data collection, but the procedures were modified for the web environment:

- making contact with the SDU;

- screening of the SDU to identify residents aged 12 or older and determining whether zero, one, or two members would be selected to complete the interview;

- obtaining consent from SDU members aged 18 or older or parental permission and respondent assent from youths aged 12 to 17 who were selected for an interview; and

- administering the NSDUH questionnaire to consenting respondents.

Details about the web-based screening and interviewing procedures, as well as the key differences compared with in-person data collection, will be provided in the 2020 data collection final report (CBHSQ, forthcoming b). Implications of the multimode data collection for 2020 NSDUH estimates are discussed in Chapter 6.

An important distinction between in-person and web-based data collection was that responsibility rested on members of SDUs to keep the data collection process moving forward to the next stages. For example, no web-based data collection occurred if SDU members did not respond to invitation letters or follow-up letters (see below). For in-person data collection, the practice was for FIs to contact SDUs regardless of whether SDU members read the introductory letter.

Also, because FIs were not present to assist SDU members with questions, an important feature of web-based data collection also was the availability of a “Contact NSDUH” link (along with a toll-free number) for technical support and answers to questions about participation in NSDUH.

As for in-person data collection, confidentiality was stressed in communications with potential web respondents. Respondents’ names were not collected with the interview data. Procedures for web-based data collection procedures were approved by RTI’s IRB before the start of data collection. The website’s https encryption provided sufficient security for information entered from devices (e.g., smartphone, tablet, computer) via any Internet connection (e.g., public Wi-Fi, cellular, at-home Wi-Fi).

Introductory letters were sent to mailable addresses20 that were selected for web-based data collection. The content of letters depended on whether SDUs had been selected for web-based data collection at the outset in Quarter 4 or whether SDUs were located in counties that started out as being eligible for in-person data collection but later became ineligible because of increased COVID-19 infection rates. Introductory letters for web-based data collection provided the website address to access the online screening and a unique participant code specific to each SDU that was needed to log in to complete screening and interviewing via the web. Web lead letters also included details about NSDUH and contained the address to the NSDUH respondent website for general information about the study and the toll-free number for the NSDUH respondent call line.

SDUs with pending screenings or interviews that subsequently became ineligible due to the COVID-19 pandemic for in-person data collection became eligible for web-based data collection. Further information on these SDUs with pending screenings or interviews will be provided in the 2020 data collection final report (CBHSQ, forthcoming b). Although SDUs could transition from in-person to web-based data collection, SDUs were not permitted to transition from web-based to in-person data collection for the remainder of 2020, regardless of decreases in COVID-19 infection rates in the counties where those SDUs were located. If an SDU transferred from in-person to web-based data collection, the SDU received a web introductory letter in the mail notifying SDU members of this change and providing the website address and participant code to access the web screening. The type of letter received at the SDU as part of this transition to web-based data collection depended on the status of the in-person data collection, such as if screening had been completed but there were pending interviews.

SDUs received follow-up letters that contained the relevant information for web participation if screening or interviewing was not completed. People from a selected SDU who called the respondent call line and stated they did not wish to participate were noted as refusals in the project database so that they stopped receiving follow-up correspondence.

Like in-person data collection, screening respondents needed to be at least 18 years old and interview respondents needed to be at least 12 years old for web-based data collection. Unlike in-person data collection, screening and interview respondents for web-based data collection also needed to be able to read English or Spanish to participate. For screenings, FIs were not available to assist web respondents, and, therefore, there may be mode differences in survey items due to respondent understanding. Also different from in-person data collection, for the main interview, respondents with limited visual ability or reading skills did not have access to audio recordings of the questions.21 Therefore, SDU members who were blind or unable to read English or Spanish were not eligible to be web-based screening or interview respondents. SDU members who did not have Internet access or access to an Internet-compatible device (e.g., smartphone, tablet, computer) also were ineligible to be screening or interview respondents via the web.

An adult resident of the SDU who chose to participate could access the NSDUH web screening instrument from any device with Internet access (e.g., smartphone, tablet, computer). As noted previously, adult residents needed to enter the unique participant code found in the web introductory letter to access the screening interview. Unlike in-person interviews, the consent process for screening involved adult SDU members reading the consent information on-screen and recording their consent online before screening could proceed. However, adults could call toll-free numbers to ask questions before consenting to screen the SDU.

Like the in-person screening, the web screening questions collected basic demographic information for all SDU members aged 12 or older for the web screening program to determine whether zero, one, or two residents of the SDU aged 12 or older were selected for the NSDUH web interview. The screening concluded if no members of the SDU were selected for an interview. If one or two SDU members were selected for an interview, these SDU members were identified on the interview selections screen according to their age and relationship to the screening respondent (e.g., 14-year-old son, 46-year-old wife) rather than by name.

If the screening respondent was selected for the main interview, the process could move forward with obtaining consent and completing the main interview. If SDU members other than the screening respondent were selected for the main interview, “handoff” responsibility rested with the screening respondent to notify other SDU members of their selection. The consent procedures for adults also applied if an adult other than the screening respondent was selected for the interview.

If one or both of the SDU members selected for an interview were youths aged 12 to 17, verbal parental permission and youth assent were required via telephone before the youth could participate in the interview. Using a toll-free number, the parent and the youth were required to call together to speak with an RTI project representative before proceeding with the interview. Once parental permission and youth assent were given verbally, the project representative recorded in the project database that parental permission and youth assent were provided for the interview. At that point, the youth interview could be accessed from the NSDUH website.

Once interview respondents used the participant code to access their assigned interview, they could choose to complete the interview in either English or Spanish. Interview respondents were encouraged to complete the interview in one sitting. Respondents were advised that they would be automatically logged out of the interview after 15 minutes of inactivity and that after 60 minutes of inactivity, all previously entered responses would be deleted for security purposes. Interview respondents also could access their interview at a later time of their choosing (until the end of the data collection period in December) by using the website address—the same address for the screening—and inserting the participant code unique to that SDU.

If SDU members did not complete the web-based interview immediately following the completion of the web screening, a follow-up letter was mailed to the sampled SDU member, addressed by age and gender (e.g., 46-year-old female resident, parent of 14-year-old male resident), after the screening was completed. If parental permission and youth assent were not obtained from sampled youths immediately following the web screening, a follow-up letter was mailed to the sampled youth’s parent(s) after the screening was completed to notify the parents of the parental permission requirement and procedures for the youths to complete the interview. Follow-up letters (regardless of SDU member age) were mailed to the SDUs once each week for 3 weeks from the day the screening was completed.

Respondents for the web-based interview, whether adults or youths, were asked to be in a private location within the home and to affirm before starting an interview that they were in a private location. At multiple points during the interview—especially before particularly sensitive sections of the interview—respondents were reminded that they should be in a private location.

As an additional layer of security, each respondent was required to set a unique 4-digit PIN code of their choosing to prevent anyone else within the dwelling unit from accessing the interview and seeing answers to questions. Because no one at RTI had access to these PIN codes, however, there was no way to assist respondents who forgot their PIN.

Every interview respondent who completed the web-based interview selected a preferred method for receiving a $30 incentive, either an electronic Visa or MasterCard gift code sent to the relevant email address of choice or a physical Visa or MasterCard gift card delivered to the SDU. Information for delivery of the incentive was kept separate from interview responses. Web-based screening and interview data that were received at RTI were stored in a heightened security network that required two forms of authentication for access.

Unlike in-person data collection, completed web interviews that were selected for verification came directly from respondents rather than from FIs. To ensure that SDU members who were selected to complete the main interview were the actual respondents who provided data, completed interview data were monitored for internal consistency to verify that SDU roster demographics reported during the screening matched those reported during the interview. Completed interviews also were monitored for situations where the self-reported age during the interview differed from the sample member’s reported age during the screening. Interviews that appeared to have been completed by someone other than the selected SDU member were removed from the dataset.

2.2.2 Notable Questionnaire Changes for 2020

2.2.2.1 Changes for the Entire Data Collection Period

Notable changes for the 2020 questionnaire that were available for the entire data collection period included the following:

- A new emerging issues section was created that included questions from the 2019 survey and new questions on specific topics, such as new topics on vaping (for any substance and nicotine), synthetic cannabinoid use, and synthetic cathinone use.

- The section included existing questions from the 2019 survey on the following topics: perceived recovery, receipt of medication-assisted substance use treatment, and kratom use.

- New questions were added for the lifetime and most recent vaping of any substance and vaping of nicotine or tobacco.

- New questions were added for the lifetime and most recent use of synthetic cannabinoids (referred to in the questionnaire for simplicity as “synthetic marijuana,” with the slang terms “fake weed,” “K2,” and “Spice”).

- New questions were added for the lifetime and most recent use of synthetic cathinones (referred to in the questionnaire for simplicity as “synthetic stimulants,” with the slang terms “bath salts” and “flakka”).

- New questions were added to measure SUD symptoms in the DSM-5 for marijuana withdrawal, prescription tranquilizer misuse withdrawal, and the symptom of craving (i.e., a strong desire or urge to use) for all substances.

- In the market information for marijuana section:

- A new question was added about purchasing marijuana from a store or dispensary.

- Respondents who reported that they last purchased marijuana from a store or dispensary were skipped out of questions for other specific settings where they purchased marijuana.

2.2.2.2 Clinical Validation Study Questions in Quarter 1

The CVS was embedded within the first quarter of 2020 NSDUH data collection to assess SUD questions that were revised to be consistent with the DSM-5 criteria for SUD. NSDUH respondents in Quarter 1 (January to March 2020) who answered the survey in English and reported using alcohol or illicit drugs in the past 12 months were randomly assigned to be asked revised SUD questions based on the DSM-5 criteria or the standard NSDUH SUD questions based on the DSM-IV criteria. Respondents who received the DSM-IV SUD questions also were eligible to receive questions in the emerging issues section of the interview for marijuana withdrawal symptoms, prescription tranquilizer withdrawal symptoms, and craving for all substances they used or misused in the past year, as described in Section 2.2.2.1. These additional symptoms applied to the DSM-5 SUD criteria but were not measured in the existing DSM-IV SUD questions.

2.2.2.3 Questionnaire Changes for Quarter 4, Regardless of Interview Mode

Several key questionnaire changes were made for the resumption of data collection in Quarter 4. Unless noted otherwise, these changes were made for both the in-person and web-based questionnaires. Key changes that needed to be made for web administration are described in Section 2.2.2.4.

- The Beginning ACASI section of the in-person interview, which guides the FI through the process of explaining important laptop keys and specific interview program functions to the respondent, was redesigned to be self-administered to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission. This modification allowed the FI to pass the laptop computer to a respondent and maintain social distancing without sacrificing necessary instructions.

- The DSM-5 SUD questions that were administered for the CVS in Quarter 1 were removed for Quarter 4 data collection in the in-person and web questionnaires due to the closure of the study. (Additional DSM-5 questions remained in the emerging issues section for Quarter 4.)

- Two questions were added to the drug treatment section to measure the use of telehealth services for alcohol or drug use issues in the past 12 months.

- A question was added to the health section to measure the use of telehealth services for health care in the past 12 months. Respondents who reported telehealth service use in the past 12 months were eligible to be asked subsequent questions in the health section that asked whether health care providers obtained information about substance use (i.e., the use of tobacco, alcohol, or specific illicit drugs) or offered health care advice related to respondents’ substance use.

- A question was added to the adult mental health service utilization section and to the youth mental health service utilization section to measure use of telehealth services for mental health or behavioral services in the past 12 months.

- All adult respondents received questions about suicide plans or attempts in the past 12 months, regardless of whether they reported having serious thoughts of suicide in the past 12 months. (In Quarter 1 and in prior years, respondents needed to report serious thoughts of suicide to be asked questions about suicide plans or attempts.) See Sections 3.4.16.1 and 6.2.3 for more details.

- Follow-up questions were added after each adult suicidality item in the mental health section if respondents reported serious thoughts of suicide, suicide plans, or suicide attempts in the past 12 months. These follow-up questions asked whether these thoughts of suicide, suicide plans, or suicide attempts were because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Suicide items were added for youths in the youth mental health service utilization section.

- These items mirrored the adult suicide items in Quarter 4, including the new COVID-19 follow-up questions.

- An additional text screen was provided for youths who reported serious thoughts of suicide, suicide plans, or suicide attempts. This text screen provided information on how to contact the National Lifeline Network.

- A series of self-administered questions related to the COVID-19 pandemic were added toward the end of the interview for adults and youths. These questions asked about respondents’ perceptions of effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their mental health, substance use, finances, living situation, and access to services.

- For the in-person interview, instructions were changed at the end of the interview to limit contact between the FI and respondent during the quality control and incentive procedures.

2.2.2.4 Questionnaire Changes for Quarter 4 Web Interviews

Far-reaching questionnaire changes were necessary for web administration. The following list includes key changes to facilitate web administration and differences between the web version of the survey and the in-person interview.

- A variable that listed whether the selected respondent was an adult or a youth was “preloaded” to the interview so that the correct informed consent information could be displayed at the beginning of the interview.

- Information about the respondent’s state of residence and sample information from the household screener (i.e., whether two people were selected at the DU and whether an adolescent aged 12 to 17 was selected) was “preloaded” because there were no FIs to enter the information.

- Information previously entered by the FI, such as language of the interview and the informed consent process, were adapted to be self-administered.

- A PIN creation process was added after the informed consent process, but before any questions, to safeguard respondent data and allow respondents to reenter the interview at a later time.

- Sections that were interviewer administered using CAPI in the in-person interviews were modified for self-administration. For example, references to showcards in the in-person CAPI sections were dropped from the web interview because those did not apply for self-administration.

- For DUs in which two people were selected, one of them was aged 12 to 17, and the second person was an adult, eligibility for the parenting experiences section was determined by asking at the start of the parenting experiences section whether the adult respondent was the parent of the 12- to 17-year-old who was selected. In the in-person interviews, this information was entered by FIs at the beginning of the interview.

- Hard errors and consistency checks were simplified throughout the interview to avoid respondent confusion and frustration.

- The web questionnaire did not include audio. Instead, pronunciations were spelled out visually on several screens, particularly for hallucinogens, inhalants, and prescription drug introduction screens, to help youths and respondents with a lower reading level understand the questions accurately.

- On-screen interviewer notes were either removed from the web questionnaire or adapted for self-administration.

2.3 Data Processing

Survey data received at RTI, either transmitted from FIs for in-person interviews or captured directly from the web-based data collection, are processed to create a raw data file in which no logical editing of the data has been done. The raw data file consists of one record for each interview. Interview records are eligible to be treated as final respondents only if people provided data on lifetime use of cigarettes and at least 9 out of 13 of the other substances in the initial set of substance use questions described in Section 2.3.1. Even though editing and consistency checks are done by the CAI program during the interview, additional, more complex edits and consistency checks are completed at RTI. Also, statistical imputation is used to replace missing, inexact, or nonspecific values after editing for some key variables. Analysis weights are created so that estimates will be representative of the target population.

2.3.1 Criteria for Identifying Usable Interviews

A key step in the preliminary data processing procedures establishes the minimum item response requirements for interviews to be used in weighting and further analysis (i.e., “usable” data). These procedures are designed to disregard data from interviews with unacceptable levels of missing data at the outset, thereby using data from interviews with lower levels of missing data and reducing the amount of statistical imputation needed for any given record.

The following criteria were used beginning with the 2015 NSDUH to establish whether interview data could be considered usable:

- The lifetime cigarette gate question CG01 must be answered as “yes” or “no.”22

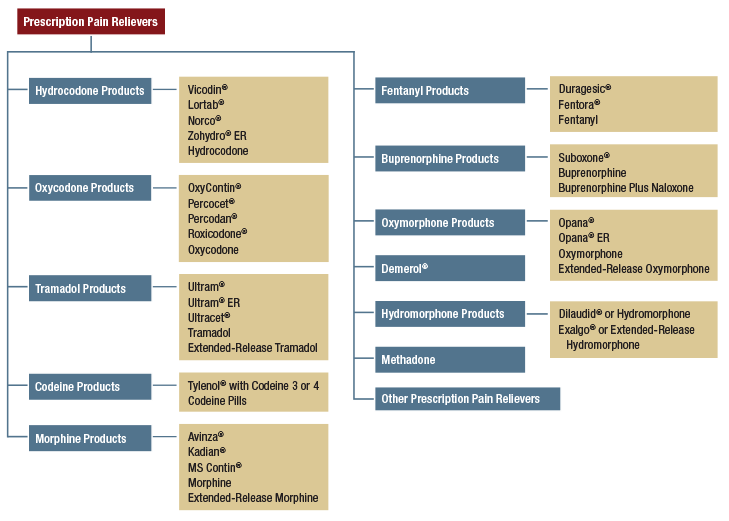

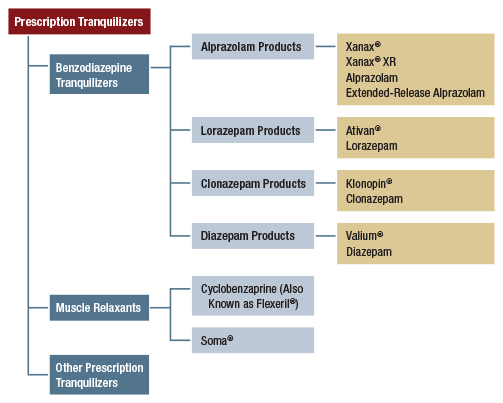

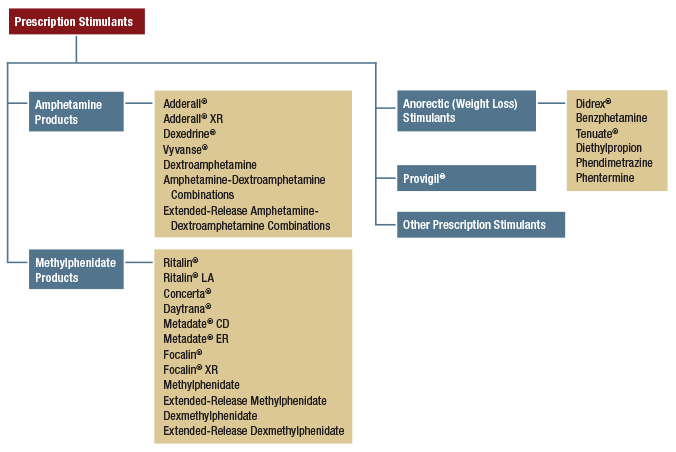

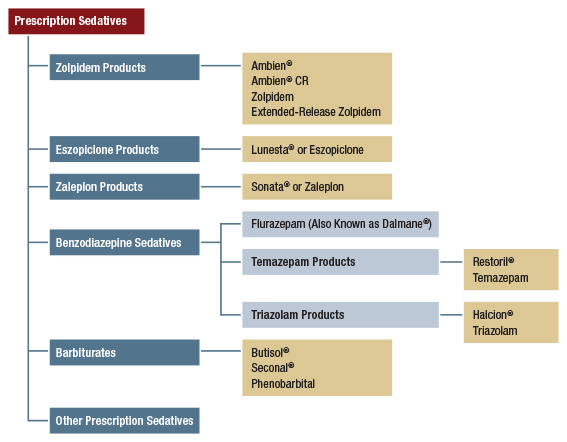

- In addition to the criterion for cigarettes, “usability” must be determined for at least nine (9) of the following other substances: (a) smokeless tobacco, (b) cigars, (c) alcohol, (d) marijuana, (e) cocaine (in any form), (f) heroin, (g) hallucinogens, (h) inhalants, (i) methamphetamine, (j) prescription pain relievers, (k) prescription tranquilizers, (l) prescription stimulants (i.e., independent of methamphetamine), and (m) prescription sedatives.

Crack cocaine was not included in the usability criteria because the logic for asking about crack cocaine was dependent on the respondent having answered the lifetime cocaine question as “yes.” Although NSDUH respondents were also asked about pipe tobacco, this tobacco product was not included in the usability criteria because there was only one other question about pipe tobacco in addition to the lifetime pipe tobacco use question. For the “multiple gate” sections for hallucinogens and inhalants, at least one gate question in the series for that section was required to have an answer of “yes” or “no.” Any of the following allowed the prescription drug data to count toward usability:

- past year use of at least one specific prescription drug in a category (e.g., pain relievers) is reported;

- lifetime use or nonuse of any prescription drug in the category is reported; or

- past year nonuse of all specific prescription drugs23 is reported, regardless of whether lifetime use or nonuse can be determined.24

2.3.2 Data Coding and Editing

The data coding and logical editing procedures discussed below applied to all respondents for 2020. The same procedures were followed regardless of whether data were collected in person (including the CVS in Quarter 1) or through the web.

Coding of answers to open-ended questions typed by respondents or FIs (the latter only for in-person data) was performed at RTI for the 2020 NSDUH. Because these open-ended questions typically include the word “other” (e.g., whether respondents ever used “any other hallucinogens,” whether respondents received treatment for their use of alcohol or other drugs in “some other place” in the past 12 months), data from these questions are subsequently referred to as “OTHER, Specify” data. For example, if respondents reported that they ever “used any other hallucinogens besides the ones that have been listed,” they subsequently could specify the names of up to five other hallucinogens that they used.

Written responses in “OTHER, Specify” data were assigned numeric codes through computer-assisted survey procedures and the use of a secure website allowing for coding and review of the data. The computer-assisted procedures entailed a database check for a given “OTHER, Specify” variable containing typed entries and the associated numeric codes. If an exact match was found between the typed response and an entry in the system, then the computer-assisted procedures assigned the appropriate numeric code. Typed responses not matching an existing entry were coded through the web-based coding system.

Elsewhere in the interview, the CAI program included checks to alert respondents or FIs (the latter only for in-person data) when they entered an answer that was inconsistent with a previous answer. For example, respondents could report that the last time they used Ecstasy was more recent than the last time they used any hallucinogen; these data triggered a consistency check to alert respondents to the inconsistency. In this way, the inconsistency could be resolved while the interview was in progress. However, not every inconsistency was resolved during the interview even if respondents were alerted to the inconsistency. For example, respondents could continue to report that their last use of Ecstasy was more recent than their last use of any hallucinogen despite being given the opportunity to resolve the inconsistency. In this situation, the inconsistency was resolved through logical editing by inferring a response for the most recent use of any hallucinogen that was consistent with the final answer for the most recent use of Ecstasy. In addition, the CAI program did not include checks for every possible inconsistency that might have occurred in the data.

Therefore, the first step in processing the raw NSDUH data was logical editing of the data. Logical editing involved using data from within a respondent’s record to (1) reduce the amount of item nonresponse (i.e., missing data) in interview records, including identification of items legitimately skipped; (2) make related data elements consistent with each other; and (3) identify inexact, nonspecific, or inconsistent responses needing to be resolved through statistical imputation procedures (see Section 2.3.3). See the 2019 NSDUH editing and imputation report (CBHSQ, 2021b) for the most recent documentation of editing procedures.

2.3.2.1 General Principles of Editing NSDUH Data

Because the CAI logic controlled whether respondents were asked certain questions based on their answers to previous questions, an important aspect of editing the NSDUH data involved identifying where questions had been legitimately skipped because they did not apply, as noted above. Examples where questions were legitimately skipped include situations in which questions applied to (1) an event (e.g., use of a particular substance) occurring at least once in the respondent’s lifetime, but the respondent previously reported the event never occurred; (2) an event occurring in a particular time period (e.g., within the past 12 months), but the respondent previously reported the event occurred less recently; or (3) respondents with a particular demographic characteristic (e.g., adults aged 18 or older), but the respondent was not part of that group. These scenarios are represented by different codes in the edited variables.

Another important principle in editing the data was that responses from one section (e.g., pain relievers) generally were not used to edit variables in another section (e.g., tranquilizers). For example, if a respondent specified the misuse of a tranquilizer as some other pain reliever the respondent misused in the past 12 months, then this “OTHER, Specify” response for pain relievers was not used to edit the data for tranquilizers. This principle of not using data in later sections to edit data in earlier sections has been important for maintaining consistent data to assess trends in outcomes of interest (e.g., substance use).25

One exception to this principle of not editing across sections involved situations in which responses in one or more sections governed whether respondents were asked questions in a later section. For example, the substance use treatment section was relevant only for respondents who reported some lifetime use or misuse of alcohol or other drugs, excluding tobacco products. Respondents who reported in the initial substance use sections they had never used alcohol or illicit drugs were not asked the questions in the substance use treatment section. In this situation, the responses from the earlier substance use sections were used to edit the substance use treatment variables to indicate respondents were not asked the substance use treatment questions because they reported they never used or misused any of the relevant substances.

2.3.2.2 Editing of Data for Tobacco through Methamphetamine

In sections of the interview for tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine (including crack cocaine), heroin, and methamphetamine, respondents were asked single questions about lifetime use or nonuse. In the hallucinogens and inhalants sections, respondents were asked a series of questions about lifetime use or nonuse of specific substances in these categories (e.g., “LSD, also called ‘acid’” as a specific hallucinogen). If respondents reported they never used a given substance, either in the single lifetime question or in the series of specific lifetime questions (depending on the substance), the CAI logic skipped them out of all remaining questions about use of that substance. In the editing procedures, the skipped variables were assigned specific codes to indicate the respondents were lifetime nonusers.

In addition, respondents could report they were lifetime users of a drug but not provide specific information on when they last used it. In this situation, a temporary “indefinite” value for the most recent period of use was assigned to the edited recency-of-use variable (e.g., “Used at some point in the lifetime LOGICALLY ASSIGNED”), and a final, specific value was statistically imputed. The editing procedures for key drug use variables also involved identifying inconsistencies between related variables so that these inconsistencies could be resolved through statistical imputation. For example, if respondents reported last using a drug more than 12 months ago and also reported first using it at their current age, both of those responses could not be true. In this example, the inconsistent period of most recent use was replaced with an “indefinite” value, and the inconsistent age at first use was replaced with a missing data code. These indefinite or missing values were subsequently imputed through statistical procedures to yield consistent data for the related measures, as discussed in Section 2.3.3.

2.3.2.3 Editing of Prescription Drug Data

In the prescription drug questionnaire sections, respondents first were asked a series of screening questions about any use of specific prescription drugs in the past 12 months (i.e., use or misuse) or any lifetime use if they did not report past year use. Respondents were then asked about misuse in the past year of any of the specific prescription drugs they reported using in that period.

Consistent with the general editing principles, an important component of editing the prescription drug variables in 2020 involved assignment of codes to indicate when respondents were not asked inapplicable questions. For example, if respondents did not report use of a particular drug in the past 12 months, then the corresponding edited variables for misuse of that drug in the past 12 months were assigned codes to indicate the questions did not apply.

Because of the structure of the prescription drug questions, respondents were not asked a specific question for their most recent misuse of any prescription drug in that general category (e.g., most recent misuse of any pain reliever). Rather, variables for the most recent misuse of prescription pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives were created from respondents’ answers to questions about the misuse of any prescription drug in the category in the past 30 days, misuse of specific prescription drugs in a given category in the past 12 months, and lifetime misuse of any prescription drug in the category. The following general principles were applied in creating the variables for the most recent misuse of any prescription drug in a given category in the 2020 data:

- Respondents who reported misuse of prescription drugs in the past 30 days were classified as having last misused prescription drugs in the past 30 days.

- Respondents who reported misuse of one or more specific prescription drugs in the past 12 months were classified as having last misused prescription drugs more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months, provided they reported they did not misuse any drug in that category in the past 30 days.

- Respondents who reported lifetime (but not past year) misuse of prescription drugs were classified as having last misused prescription drugs more than 12 months ago, provided (1) they answered all applicable questions about misuse of specific prescription drugs in the past 12 months as “no”; or (2) they reported any use of prescription drugs in their lifetime and they explicitly reported they did not use any prescription drug in that category in the past 12 months.

- Respondents who reported they never used or never misused prescription drugs were classified as never having misused prescription drugs. (The coding of the variables for most recent use did not distinguish between respondents who never used prescription drugs and lifetime users who never misused prescription drugs.)

As for the substances discussed in Section 2.3.2.2, some respondents provided indefinite information on when they last misused prescription drugs. For example, if respondents reported misuse of one or more specific prescription drugs in the past 12 months but they did not know or refused to report whether they misused any prescription drug in the past 30 days, it could be inferred these respondents misused prescription drugs in the past 12 months and potentially in the past 30 days. In these situations, a temporary “indefinite” value for the most recent period of misuse was assigned to the variables created for the most recent misuse of pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives (e.g., “Used at some point in the past 12 months LOGICALLY ASSIGNED”), and a final, specific value was statistically imputed.

In addition, respondents were instructed in the prescription drug sections not to report the use or misuse of over-the-counter drugs. Therefore, if a respondent’s only report of misuse in the past 12 months was for an over-the-counter drug, the respondent was logically inferred not to have misused any prescription drug in that category in the past 12 months. These respondents were not asked about lifetime misuse of any prescription drug in that category because the CAI program handled them as though they had misused prescription drugs in the past 12 months. Consequently, statistical imputation was used to assign a final value for whether these respondents misused prescription drugs more than 12 months ago or never in their lifetime.

2.3.2.4 Editing of Mental Health Data

An important aspect of editing the mental health variables was documentation of situations in which it was known unambiguously that respondents legitimately skipped out of the corresponding questions. These included situations in which respondents were not asked questions based on their age and those based on routing logic within a given set of mental health questions. For example, if adult respondents reported they did not stay overnight or longer in a hospital or other facility to receive mental health services in the past 12 months, the CAI logic skipped them out of all remaining adult mental health treatment utilization questions about inpatient mental health services. In the editing procedures, the skipped variables were assigned codes to indicate these additional inpatient adult mental health services variables did not apply.

As noted in Section 2.2.2.3, all adult respondents beginning in Quarter 4 (i.e., beginning in October 2020) received questions about suicide plans or attempts in the past 12 months, regardless of whether they reported having serious thoughts of suicide in the past 12 months. Before Quarter 4 and in prior years, respondents needed to report serious thoughts of suicide to be asked questions about suicide plans or attempts. Consequently, more adult respondents in Quarter 4 were asked questions about suicide plans and attempts in the past 12 months. Therefore, two sets of edited variables were created for 2020 for the affected suicide measures. The first set was defined for respondents interviewed prior to October 2020 and retained the skip logic before the questionnaire change in Quarter 4. The second set was defined for respondents interviewed in Quarter 4 (i.e., October to December 2020) and took into account the new skip logic. The second set of edited variables will be used in future years because this change in Quarter 4 of 2020 will apply to all adult respondents for the 2021 NSDUH.

2.3.3 Statistical Imputation

Imputation is defined as the replacement of missing values with substituted values. For a subset of NSDUH variables, missing data are replaced with statistically imputed data after editing is complete. This section provides an overview of the statistical imputation procedures implemented for the 2020 NSDUH. Section 2.3.3.1 discusses the general approach to imputation. Section 2.3.3.2 discusses modifications to the imputation procedures to account for special issues in 2020.

2.3.3.1 General Imputation Approach

For substance use, SUD, demographic, and other key variables still having missing or nonspecific values after editing, statistical imputation was used to replace these values with appropriate response codes. The mental health variables related to mental health service utilization, suicidal thoughts and behavior, and major depressive episode used in reports and tables were not imputed. See Sections 3.4.7.4 and 3.4.7.5 for discussion of how missing data were handled for variables for psychological distress and impairment due to psychological distress among adults. These variables were important for prediction of any mental illness and serious mental illness in the past year among adults.

The remainder of this section discusses procedures for substance use and other variables that underwent statistical imputation to replace missing or nonspecific values. For example, a response is nonspecific if the editing procedures assigned a respondent’s most recent use of a drug to “Used at some point in the lifetime,” with no definite period within the lifetime. In this situation, the imputation procedure assigns a value for when the respondent last used the drug (e.g., in the past 30 days, more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months, more than 12 months ago). Similarly, if a response is completely missing, the imputation procedures replace missing values with nonmissing ones. See the 2019 NSDUH editing and imputation report (CBHSQ, 2021b) for an overview of the general imputation process.

For most variables, missing or nonspecific values are imputed in NSDUH using a methodology called predictive mean neighborhood (PMN), which was developed specifically for the 1999 survey and has been used in all subsequent survey years. PMN allows for the following: (1) the ability to use covariates to determine donors is greater than that offered in the hot-deck imputation procedure, (2) the relative importance of covariates can be determined by standard modeling techniques, (3) the correlations across response variables can be accounted for by making the imputation multivariate, and (4) sampling weights can be easily incorporated in the models. The PMN method has some similarity with the predictive mean matching method of Rubin (1986) except, for the donor records, Rubin used the observed variable value (not the predicted mean) to compute the distance function. Also, the well-known method of nearest neighbor imputation is similar to PMN, except the distance function is in terms of the original predictor variables and often requires somewhat arbitrary scaling of discrete variables. PMN is a combination of a model-assisted imputation methodology and a random nearest neighbor hot-deck procedure. The hot-deck procedure within the PMN method ensures missing values are imputed to be consistent with nonmissing values for other variables. Whenever feasible, the imputation of variables using PMN is multivariate, in which imputation is accomplished on several response variables at once.

For most variables starting a new baseline for trends in 2015, a modified version of PMN was adopted and continued to be used for these variables in 2020. This procedure also was adopted for all SUD variables beginning in 2020.26 In addition, the questionnaire since 2015 has included questions about any use of prescription drugs in the past year and lifetime periods (i.e., not just misuse of prescription drugs). Consequently, imputation-revised variables have been created since 2015 using this modified version of PMN for any use of prescription pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives. Levels in these new variables indicate any past year use, lifetime but not past year use, and lifetime nonuse. Because of changes in how respondents are asked about the initiation of misuse of prescription drugs, imputation-revised variables for the age at first misuse and the date of first misuse have been created since 2015 only for past year initiates. For nonprescription drugs and for prescription drugs prior to 2015, age at first use (or misuse) and the date of first use (or misuse) were created for all lifetime users of the drug of interest.

While still utilizing the model-assisted imputation methodology described previously, modified PMN involves collocated stochastic imputation (CSI)27 for categorical variables based on the predicted probabilities from the modeling step. Under modified PMN, nonspecific or missing values for continuous variables are still assigned using a donor selected from a hot-deck procedure. One benefit of modified PMN is the ability to cycle through a group of variables being imputed as a set. This cycling process allows variables imputed later in the sequence to be used as covariates in the modeling process for variables earlier in the sequence, thus reducing the importance of imputation order.

Variables imputed using PMN for 2020 were (1) the initial demographic variables; (2) substance use variables for cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, cigars, pipe tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, crack, and heroin (recency of use, frequency of use, and age at first use); (3) income; (4) health insurance; and (5) demographic variables for work status, immigrant status, and the household roster. Variables imputed using modified PMN for 2020 were the drug use variables for hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives (recency of any use, recency of misuse, frequency of misuse, past year initiation status, and age at first misuse among past year initiates of misuse). Additionally, modified PMN was used in 2020 to impute variables related to DSM-5 SUD outcomes28 (i.e., past year disorder and disorder severity) for alcohol and illicit drugs and the most recent use of the following: vaping of any substance, nicotine or tobacco vaping, kratom, synthetic marijuana, and synthetic stimulants.

In the modeling stage, the model chosen depends on the nature of the response variable. In the 2020 NSDUH, the models included binomial logistic regression, multinomial logistic regression, Poisson regression, time-to-event (survival) regression, and ordinary linear regression, where the models incorporated the sampling design weights.

In general, hot-deck imputation replaces an item nonresponse (missing or nonspecific value) with a recorded response donated from a “similar” respondent who has nonmissing data. For random nearest neighbor hot-deck imputation, the missing or nonspecific value is replaced by a value from a donor respondent who was randomly selected from a set of potential donors. Potential donors are those defined to be “close” to the unit with the missing or nonspecific value according to a predefined function called a distance metric. In the hot-deck procedure of PMN or modified PMN for continuous variables, the set of candidate donors (the “neighborhood”) consists of respondents with complete data who have a predicted mean close to that of the item nonrespondent. The predicted means are computed both for respondents with and without missing data, which differs from Rubin’s method where predicted means are not computed for the donor respondent (Rubin, 1986). In particular, the neighborhood consists of either the set of the closest 30 respondents or the set of respondents with a predicted mean (or means) within 5 percent of the predicted mean(s) of the item nonrespondent, whichever set is smaller. If no respondents are available who have a predicted mean (or means) within 5 percent of the item nonrespondent, the respondent with the predicted mean(s) closest to that of the item nonrespondent is selected as the donor.

In the univariate hot-deck situation (where only one variable is imputed), the neighborhood of potential donors is determined by calculating the relative distance between the predicted mean for an item nonrespondent and the predicted mean for each potential donor, then choosing those means defined by the distance metric. The pool of donors is restricted further to satisfy logical constraints whenever necessary (e.g., age at first crack use must not be less than age at first cocaine use).

Whenever possible, missing or nonspecific values for more than one response variable are considered together when using hot-deck imputation to select a donor. In this (multivariate) situation, the distance metric is a Mahalanobis distance, which takes into account the correlation and heterogeneous variances between variables (Manly, 1986), rather than a Euclidean distance. The Euclidean distance is the square root of the sum of squared differences between each element of the predictive mean vector for the respondent and the predictive mean vector for the nonrespondent. The Mahalanobis distance standardizes the Euclidean distance by the variance-covariance matrix, which is appropriate for correlated random variables or those having heterogeneous variances. Whether the imputation is univariate or multivariate, only missing or nonspecific values are replaced, and donors are restricted to be logically consistent with the response variables that are not missing. Furthermore, donors are restricted to satisfy “likeness constraints” whenever possible. That is, donors are required to have the same values for variables highly correlated with the responses. For example, donors for the age-at-first-use variable are required to be of the same age as recipients, if at all possible. If no donors are available who meet these conditions, these likeness constraints can be loosened. Further details on the PMN methodology are provided by Singh et al. (2002).